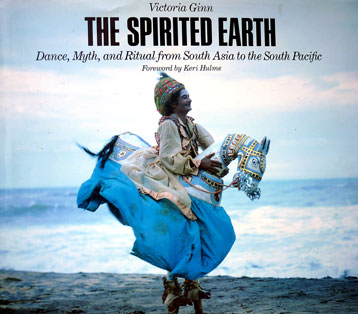

Photo by Victoria Ginn from

"The New Zealand Series "

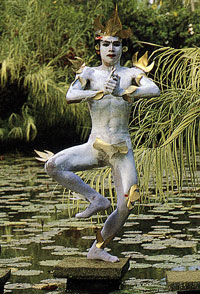

Sanghyang Tjintiya, "the

divine slippery one", an

androgynous god in Bali.

Photo by Victoria Ginn.

The bear king Jambava defeats marauding

demons (Karnataka, India).

Photo by Victoria Ginn.

(Karnataka, India).

Photo by Victoria Ginn.

Aborigines in Arnhemland, Australia.

Photo by Victoria Ginn

Senge Dradog, the emanation of

compassionate wrath (Tibetan

Bhuddist in Northern India).

Photo by Victoria Ginn.

Victoria Ginn was born in her Grandmother's house in the suburb of Thorndon in Wellington, New Zealand. Victoria always felt a strange relationship with the ghost of writer Katherine Mansfield because they were born in Thorndon on the same day, October 14, and Grandmother and Katherine Mansfield's mother used to play the ouiji board together. Grandmother was a strict Victorian. She was also an opera singer and teacher. She was highly respected and held regular salons. Madam Ginn they called her.

Victoria was educated at a private girls' Catholic school, St Mary's, at the same time as she lived with her Grandmother. Victoria divided her time being an obedient granddaughter and a rebellious schoolchild. At that time St Mary's had boys in the primary school and Victoria made friends with some of them in the classroom. That made things a little more balanced for her.

Her mother was a painter and an actress and was considered eccentric. Thank goodness, thought Victoria. She loves her mother, her flamboyant personality and the acting drama she carries over into everyday life. Victoria has a strong artistic influence from the women's side of her family. Her father was an insurance broker.

Even before she went to school, Victoria had started to develop her own philosophy about life. She made friends with many different types of insects, birds and animals. It started off with a fascination with the lowly life of worms, ants, katydids and wetas. They were all her pets. Then she worked her way up through to geckos and lizards.

She had human friends too, they used to have their clubs and associations, and so on, but the creatures were a special area which no human could come near. It wasn't a secret but it was a very private thing. She was protective and possessive over what she called her little children, her spirit friends. She discovered they had just as much personality in their way of life as human beings, but were somehow more attractive, more interesting.

As she grew older, the animals grew larger. When she was 10 she was keeping birds that she'd rescued or nabbed from nests, a blackbird or a thrush or a sparrow. Later on it became opossums, and magpies. She brought them up from infant stage. She was their mother. They were always very free. She would take them out to the garden, and sometimes to school, hidden deep inside her. If she was mothering a small opossum she would keep it with her in her clothes. It was really fun. The kids would often find out and sometimes the teachers would too.

She's not sure now why she did that, but it gave her a sense of sanity, a type of vision other than the education being given her by the nuns of the school. She could never quite believe in school. She had an different attitude to life. She could never believe what she was being taught. She had already decided she was going to choose her own way. When she read A.S. Newell and Krishnamurti at the age of 13, she found an affirmation of the path she'd decided on. Then at 14 and a half she discovered Karl Jung, and Conrad Lawrence. She felt her way of perceiving life was correct and had some deep truth in it.

Another part of her life, outside of school, was spent around the coastal landscape. Her mother gave her children a lot of freedom and they lived very close to a wild part of the ocean with lots of hills. Her parents had a place in Titahi Bay and Victoria grew up there, in between staying with her Grandmother in Thorndon while she was going to school.

It was a split sort of life. At Titahi Bay it was like a savage alternative lifestyle, doing all sorts of crazy things around the coasts, wild rather than primitive, and really, really curious. In this way she slipped away from this modern civilization, this way of seeing life in only one dimension.

Her inheritance of contradictions from her family opened up other ways of seeing. She became aware of phenomena that were not perceived to be part of reality or to have any impact on reality in itself. Her dreams became part of her experience.

In her latest work, which resulted in her book of photographs The Spirited Earth (Rizzoli New York, 1990), she found that other peoples did offer ways of maturing through their initiation ceremonies. But in Western civilization you go through baptism when you're an infant and that's it, you're cleansed. If you have a good life, if you're a loyal and obedient citizen to the ruling powers, your place in heaven is guaranteed.

She was introduced to photography by a family friend who took photographs of her and other children. He didn't show her how to take photographs, but he let her borrow the camera, a 35mm Leica. She taught herself. She can still remember the first photograph she ever took. Victoria thought it was wonderful. A wild seagull was attacking her friend. In the frame you can see the beautiful wings of the bird brushing over the head of somebody whose hand is reaching out. A powerful image of a bird in a form of attack. She was 16 when she started taking photographs. She went looking for stark, dark images in black and white. Some of them definitely had a feeling of - doom is not the right word, but a quality of darkness.

She read a lot, but she never looked at photography books. She had no formal training. She found out about exposures and the tricks of the trade by trial and error. She used to print her own images but never very well. She was aware of her failings there. She got good images but she couldn't print them well. She used to love going into the darkroom after travelling. After getting intensely involved with people, tribal people, myth people, she could withdraw into the dim silence, and bring herself back in. Now that she photographs in colour, with its more demanding developing process, she doesn't print her own photos any more.

She was never a commercial photographer. She showed prints to her friends and had a few exhibitions, but she never sold any. School hadn't educated her on how to market herself. In her early work in New Zealand she used to choose certain individuals and befriend them. There was an old lady who lived up Aro Street in a dark damp valley with dilapidated wooden houses that had the paint peeling off. The old lady was covered with warts, the skin on her face and neck sagged and bulged with the weight of them. When Victoria was 20 she photographed the old lady eating and became her friend. She could see such a power in the old lady's ravaged face. It had an immense amount to say.

On her journeys through Afghanistan and Pakistan Victoria noticed how the maimed and retarded were treated. There was a sense of sacredness surrounding them as the crowds surged backwards and forwards around them with ceaseless energy. Those were the sorts of people she was drawn to. Not necessarily maimed, just a quality that she sought. It might be a smile that seemed to be extremely pure, rich in something, where the soul seemed to shine through, where there was no artifice or half life. It may be somebody who'd become mad, but there remained a pure sense of that person's self even though they'd lost consciousness of their personality. That didn't matter. Personality to Victoria was a superficial thing. She wanted to get behind personality, that obvious self we coat ourselves with to keep going, to fuel our sense of belonging.

Then she became interested in the show and play of light, and what effect it had on mood and emotion. She felt she was dealing with a universal archetypal language of the individual. Her early work repelled many people because it was stark, black and white, full-on, with nothing oblique. To her the world was full of zombies, a land of concrete and gray suits and stiff staring faces that never met you with honesty. The only people who contained the real purity of life were people who didn't belong to "normal" society. This was her view of New Zealand in the 1970s.

She thinks the spirit of the people has gone from the New Zealand bush. They're no longer picking the berries. You don't meet them on the paths in the bush dressed in beautiful leaves walking with lovely grace and smiling faces. New Zealand had a sense of terrible loneliness in its hills. At the same time, she refused to be defeated by that. Because that's where she belonged. This was the country she had been born into.

But first she had to get out. She felt she was only going round in circles, little circles in a little country. She left when she was 19 and went to England and Canada, finishing up in Florida with an aunt who taught her the proper ways to dress. She was suddenly blasted out into the great wide world and she started to notice the effect on people of how one dressed, the differences in attitude that resulted. She was in Florida amongst a closed circle of retired millionaires. She would have shamed her relations if she'd kept to her own indifferent ways of dress. She didn't want to do that, she wanted to show respect. She allowed herself to be remoulded for a time. She didn't wear a ring in her nose anymore.

On her second journey, a couple of years later, she went to South-East Asia and there she was introduced to the life of the night. It was quite different to anything she'd experienced before. It was a kind of wonderful chaos. She was at a romantic age and was open to the mystery and all the excitement. She wanted to explore and take photographs. She wanted to open up her whole self. Photographing was her way of responding to people.

When her Grandmother died Victoria took over the house in Thorndon. It became her base. She took in boarders but tried to retain its sense of home. She kept the music room. The house had a wonderful sense of atmosphere. She needed that base. She always needed a long period of rest after her adventures travelling. She didn't go on package tours. Her travels were open to the winds. Whatever happened, happened. They were rich in adventure, with touches of drama and confrontation. She used to leave for relatively short trips, six or eight months, just exploring or trying out another lifestyle. Then she'd come back to the house.

One trip took her to Papua New Guinea. It was her first really beautiful experience with another people. She didn't know where she was going but somehow she ended way up on the border between Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea where the Hulo tribe lived. She seemed to have stepped back into pre-history. All her early life disappeared, vanished. She couldn't speak their language, but she didn't need speech, she didn't need to talk. The tribe communicated silently, through the eyes, through face reading, through gesture, through gut reaction. In this way she met a lovely people who in their own tiny space seemed to go back fifty or sixty thousand years.

She fell into that space. It was like falling into a time warp. They were a pure people. They had something that had never been altered. They had a sense of identity, a sense of belonging to their land and to the spirits and to the magic of the place. She spent only a few months there, but it was enough. It could have been an eternity because the experience was so intense.

In New Zealand time had just drifted by. In a year she may have had only three or four experiences that had an intense effect upon her and remained in her life for a number of years. But when she travelled, in a month she could experience something that seemed to cover a whole lifetime because it was so full. It was a blast.

She used to go on journeys in her dreams too. She had epic dreams that she would remember for years afterwards. Sometimes she found, when she went on a journey, especially in Afghanistan, that she had already been there. She recognised, not the cities, but the landscape, because she'd seen it already in one of her dream journeys. It happened in Australia also, in the Northern Territories, the ancient and wild areas of the outback there. Her dream journeys were the other half of her travelling self. She never dreamt when she was travelling. She sometimes grew weary of having to travel physically because she knew of this other way. But she had to travel physically in order to bring something tangible back.

She had the power to read minds for a time after coming out of Papua New Guinea. She had a sense of horror as she looked at people. She witnessed the deterioration of some artist friends. They were writers and musicians. She saw them decline into insanity while nobody seemed able to help. There was nothing to nourish the soul. She watched madness encroaching on people with highly refined sensitivities. One was a particularly close friend. She felt very quickly she had to escape.

Then it happened that she became a prisoner of the Afghanistani justice system. Fortunately she made a friend who became her helper. He was a landowner and a doctor, an intellectual, part of the old aristocracy. He had to pretend to be an interpreter from the British Embassy, otherwise he couldn't be seen with her. He helped her fight to get her freedom back. It was 1978, when the Russians moved in and the revolution began. Because she had to organise her own trial she witnessed what was going on. She was moving in and out of the ministries and courts of justice and meeting with judges and prosecutors.

The very day the Russians invaded she was sitting with her helper in the Supreme Court Chambers. They watched the leader of his outlawed political party being arrested and brought in. Two other senior members of his illegal party had just been shot. When her helper saw the leader being taken in, he thought that was it. That was their only hope for a more democratic government. He was full of despair.

They went out and sat in a coffee bar where they could talk. He said, "I will raise the people of my area. I can raise 70,000 soldiers." He was so upset. "I'm going to organise a revolution," he said.

She told him there had to be another way. "It's not the way to go," she said. "It won't work."

That afternoon Victoria met her judges. She had afternoon tea with them, sitting on soft cushions in a big courtroom with High Court judges dressed in turbans. They assured her that she'd be let free the day after next. Victoria went back to the cheap hotel she was staying at and thought, "At long last."

She'd had so many false hopes. From the day she was imprisoned they would say, "Tomorrow you're going to be released." They would pull her to the grate and say, "Tomorrow you'll be let go." Tomorrow would come and the guards would lead her to the courts where there were 40 or 50 prosecutors, and maybe one could speak English. They would discuss her case with the one that could speak English. Then he would tell her what they were going to do. They were debating whether she should have a trial or whether she should just be left in prison. They were going to take her cameras away. They tortured her in this way and reduced her to tears.

This went on daily. And every day she'd think, "Maybe tomorrow I'm going to be free."

Eventually she got out on bail. She had to stay in a special hotel on the outskirts of Kabul. A cheap single-story mud cottage that cost only 20 cents a night.

When she was in prison she was safe. She was protected by the women. When she was out, she wasn't protected by anybody. She was at the mercy of prosecutors or anyone who had her file. She was a prisoner of 200 clerks and prosecutors and judges. They knew that when they had her file they had complete power over her. Being white, not Muslim, an unmarried woman, supposedly guilty of a crime, she was nothing. When you're in a state of nothing, how can you protect yourself against the huge army of lust and hatred that was thrown at you? She would have preferred to have stayed in prison.

Victoria was sitting in the courtyard of the hotel, on the outskirts of the city, drinking a cup of tea when she heard guns in the distance. She had said goodbye to her helper, and the judges had said, "Tomorrow." This time it was going to happen.

She thought, "Now, for the first time in weeks I can relax." A servant boy brought her tea. Usually it was rich in sugar but she didn't buy sugar this day. Big fat ants climbed up her legs to drink her perspiration because it was so hot. She didn't mind the ants crawling up her legs. They could crawl all over her because the next day she was going to be free.

Then she heard the guns. They kept coming closer. After half an hour or so, when the servant boy came round with another cup of tea, she asked him, "Is this a celebration, all these guns?" Because the only time she had heard guns was back in Wellington on Queen's Birthday weekend. They sounded like the same guns - boom, boom.

"No, no, no," the boy replied. "Revolution."

Victoria sat there. She couldn't believe it. It just didn't register. She'd never been in a revolution. Revolutions belonged to history, in schoolbooks.

The booming came closer. After a while she heard a roaring up and down outside the hotel. She thought, "They have tanks moving around out there. I better go and have a look."

She didn't have her own camera, so she grabbed one from some Danish tourists who were in the hotel. Right outside the gate there was a tank with the tank driver poking out of the top. The driver looked like he was part of the metal, his body was so rigid, an angular, stiff tautness about him. She thought, "This is amazing to see, a man and machine become so much at one. I want to photograph it." It wasn't for political reasons, it was just the image. The servant boy was waiting behind her because he wanted to shut the gates.

But as soon as she lifted up the camera, a White Russian soldier jumped out of nowhere and grabbed her wrist. He hissed in her ear, "If you take one picture, you're dead."

She thought, "What?" It didn't register. The servant boy grabbed her camera. He was going to throw it on the ground. It wasn't even her camera. He was shrieking, "No, no, no, no, no."

She backed away towards the gates. As she backed off, she looked up the street and saw an exodus of people. She realised she had seen it already. She had dreamt about it a couple of years before. All the pieces of her dream were coming together. A huge exodus of people going out of the city. The street was closed. All the shops were shut, everything was barricaded and the people were gone.

Soldiers were swarming over the hills, like the red ants that climbed up her legs. They were coming over the hills around Kabul in their thousands.

She couldn't leave. It was too late. She couldn't get out of her street. They were lining up for war. She'd never been so frightened in her life.

A couple of people dashed in just before the gates closed on them. They were absolutely stricken. They'd just seen people being ripped in half by tanks rolling up and down the streets, not caring about civilians. They'd watched little boys being shot when the machinegun fire started. They were in a state of shock. "This is death," they cried. "Death is coming."

All the noises you hear in war films and documentaries erupted around her, the bombs whizzing through the air, and the deadly silence. They bombed the palace close by and there was heavy ground fighting. Every form of artillery made since the Second World War seemed to be taking part. Debris was falling everywhere. The people in the hotel, and the Danes, were huddled together. She thought it would be her last image of civilised people, all huddled together as a group, sheltering like animals in a corner of the hotel. Everything in the hotel was trembling.

Victoria went back to her room. The hotel was only a shack made of mud and straw divided into mud rooms. There was no protection.

Bombs fell everywhere. The hotel shook.

Then the jets screeched overhead. That's when she dived under her bed. The bed was about a foot off the floor, built of matted, woven straw. She discovered that if there's anything in modern warfare that's designed to destroy one's courage, it's the sound that low-flying jets make when they bomb. It's not the bombs themselves. It's the scream of the machine. The shriek as it dives only 50 feet overhead. The noise shattered her body and her nerves. She couldn't control herself because of the horrendous sound.

They bombed all night. For four days no one could go out. It had started on a sunny day, but as soon as the fighting began great clouds covered the sky over and it rained continuously. Just like that. Up till then it had been one long series of hot sunny days.

Victoria had nightmares for months after Afghanistan. If she wasn't being visited by ghosts, she was having dreams of the land filled with flames, or trying to escape from bombs, or hounded by prosecutors, or people pointing guns at her just about to shoot. It seemed there was nowhere in New Zealand, no one, nothing, to lead her forward into some more positive atmosphere. She had to create her own healing. She had to reconnect with life. She turned to the landscape and to the human spirit, the soul, the emotional self, reacting to and with the landscape.

That's where her colour work came from.

She became hyperconscious of life. Black and white was too interior. Now she wanted to see the skin of life, to feel the blood of life, to see the heart. She was responding in a different way, or perceiving in a different way fromher black and white photography. She had to cleanse herself of an evil that had been absorbed.

It went right back to the sense that the landscape shouldn't be alone. It was like the religious belief of ancient Indian philosophy, that nature has to be stimulated by the souls of humans interreacting with it. It was like being out on a mountain and your eyes are filled with the vision that you see. She wanted to say, "Where am I in this? Where is the emotion? Where is the human response?"

Maybe it wasn't even that. Maybe she was just trying to place herself in that land. That's why figures appear in her next work, The New Zealand Series, colour landscapes populated by strange fantastical human shapes. A trouserless jester dancing on wheat stubble. A naked figure submerged motionless in a tidal pool. A savage mud-caked madman baying at a gathering storm. It is like they're uniting in a psychic or sexual sense with the earth.

It was her way of healing. She couldn't passively sit and watch the land. She had to participate in it too. Or perhaps those strange figures were her artist self, doing it abstractly. In the same way the aboriginal man became the cassowary, the participation of the human soul with the soul of the earth. Healing requires the assistance of the force of nature, or the force that might be contained in an animal. Karl Jung has said nature is the one that cures, without which we are a neurotic animal.

That's one reason she put the figures in. But it was also because they looked right.

All that had happened before was like an initiation. All her experiences were a process of learning that prepared her for something else. Every work led to another work.

This time the journeys took more than three years, from 1984 through 1987. She had to return to New Zealand to restock and refinance. But it was all part of the same effort.

She finished up with representations from many different cultures. She went through parts of Indonesia. In Bali she found a lot of village beliefs and performance ritual, and the classical forms of dancing, storytelling through dance and drama left over by the reign of past kings. Myths were passed on by the courtly dance of Java. She was looking for the essence of what was behind the performance, the quality of the character, and what that represented on a psycho-spiritual social level.

She went into Sumatra and saw how they expressed their relationships to the land. Everything is linked to the sun or the moon or the ocean, or to the birds or animals, or to spirits of some form or other, or to gods or deities, energies within the psyche. She went through Sarawak up the rivers into the jungles and visited the various tribes. She happened, by chance, on major celebrations where people were seeking through their dances and rituals to unite with the various divinities of the jungle and sky.

She went through Thailand with its classic dance which served as a platform for the mythic characters of some of the great epics of Asia, the mythic epics of their religious history. On to Burma and Nepal and the religious festivals with their rituals, masks and forms of metamorphosis. Then into the Himalayan area of northern India with the Tibetan tantra, into the desert regions of central India, dwelling amongst tribal people and seeing their classical forms of religious expression that have been transformed through dance, becoming more like popular dance than the religious performance it used to be, but still retaining its sacred message.

The next journey took Victoria to northern Australia and north Queensland amongst the various aboriginal tribes there. Then over into the Solomon Islands where she was a visitor and guest of tribal people. Down into Vanuatu where you're not allowed to do these things without permits.

She didn't know a lot of the stories, the meanings, behind the ritual actions. When she took the photographs, she didn't know why she wanted the sea to be there, or why she wanted fire to be in the image. It was intuition. Later, when she researched them and found out their meanings, it all made sense. Every time. She would sense a delight in the performers when she suggested showing somebody representing the myth of the bird Garuda, the energy symbol for the Vedic Hindu god Vishnu, against a waterfall. It turned out the waterfall is Garuda's symbolic opposite which he is integrally involved with.

Each part of the journey prepared her for the next. She couldn't have done the second journey first. She wouldn't have had enough sensitivity. The Asians were a bit more flexible with her idiosyncracies and ignorance. All the while she became more sensitised. She had the feeling the gods and goddesses were looking after her. She still has that feeling.

All these journeys resulted in a book of photographs, The Spirited Earth: Dance, Myth, and Ritual from South Asia to the South Pacific, containing more than 160 colour photographs. It was published in November 1990 by a leading international publisher, Rizzoli in New York.

When Victoria went into a village they always took about a week, seeing what she was like, testing her. They would then decide whether to show her anything. She followed her intuition the whole time. She felt so often that she was one of them. She felt more at home - a strange feeling - than she did when she returned to New Zealand. She went into villages and met performers and priests and paramount chiefs who always greeted her with a form of ritual. It was body language and spontaneous reaction. She conjured up a lightness of being. A complex message was sent out through invisible antennae. Sometimes it was a sense of being embraced and embracing in return. She'd been expected. It was like that. She was meant to come, that was the feeling.

She was always being tested. The Tibetan Buddhists in northern India had amazing psychic qualities and powers. They tested her all right. She hates heights, they terrify her, but she had to go over the highest navigable pass in the world to try and find them. She didn't know why she was going there but she had to go.

She found herself in a bus winding up over a mountain trail teetering over sheer drops of five and ten thousand feet. The bus often had to go backwards in reverse, and cringe around one-lane unsealed surfaces to let lorries pass. The Tibetan passengers were all praying, using their prayer beads to get them safely over the mountain. Her eyes fixed with terror on the weaving of the woman's shawl sitting in front of her. She still has imprinted on her mind the detailed weaving of that shawl.

She climbed up to the monasteries perched high up on the mountain ledges in a valley leading into Tibet. When she got there, she found that the monks had all disappeared to go begging. They'd only just left. She had to go back over the mountain empty handed.

She went to the headquarters of the Dalai Lama in northern India, to Dharamsala where they had their refugee center. The monk in charge sent her in search of another monastery further down. This time the lamas and monks were there, praying. They were using the oldest, most pure form of Tibetan buddhist tantra that still exists. They told her she could take photographs but she had to come back in a few days' time after they'd finished their prayer sessions.

Every time she tried to return, the bus would break down. Day after day she set off for the monastery. Night after night she ended back up in Dharamsala.

In desperation Victoria went to the monk's office again. She told him, "There's something stopping me."

He said, "The greater something is, the more obstacles that will be placed in your way." He was trying to tell her she was meeting a power in these people, and that they would let her know when she was ready to come.

The change came after her final test. This time not only the bus broke down, but the taxi bringing her back broke down also. Victoria had to walk back up through the night, through the jungle bush. She'd crossed the mountain, feeling terrified again, then hired another taxi. It too broke down part way up the road to Dharamsala. She thought, "I'll have to walk back."

It was about six miles and she couldn't see. It was a pitch black night. She had to shuffle up the road listening to all the weird sounds coming out of the bush. There were crashes in the trees and the hoots and calls of baboons. She was tense and fearful, stumbling along in the blackness. She heard unfamiliar eerie sounds and thought, "What sort of monsters are these?"

After a while she began to relax. She thought, "I belong to this night, too. I'm all right. I'm a creature, they're all creatures. Nothing's going to hurt me."

She saw lights ahead of her. It was the Indian Hindu festival of lights and the village street with its little buildings was lined with candles. She came into the light with all these candles burning.

As she came out of the darkness the first thing she saw was a little child, dancing in the middle of the road. It was like a gift, something to lighten her burden. The child was dancing a dervish dance, or a Tibetan whirl dance, spinning himself around with a beautiful movement, then flipping himself over in circles, his many shadows skipping around him in the candlelight. It was exquisite.

She thought, "Here's my greeting. What a delight!" The child gave her a lovely sense of joy. She'd gone through her fear and found a state of peacefulness. She felt a change in her attitude.

When she tried to go down again the next day, it was all right. She had been the obstacle. It had been a form of initiation.

This time she reached the monastery without incident. She was content with the magic in her life.

1990

Tamu Nadu, India. Photo by Victoria Ginn

Victoria was educated at a private girls' Catholic school, St Mary's, at the same time as she lived with her Grandmother. Victoria divided her time being an obedient granddaughter and a rebellious schoolchild. At that time St Mary's had boys in the primary school and Victoria made friends with some of them in the classroom. That made things a little more balanced for her.

Her mother was a painter and an actress and was considered eccentric. Thank goodness, thought Victoria. She loves her mother, her flamboyant personality and the acting drama she carries over into everyday life. Victoria has a strong artistic influence from the women's side of her family. Her father was an insurance broker.

Even before she went to school, Victoria had started to develop her own philosophy about life. She made friends with many different types of insects, birds and animals. It started off with a fascination with the lowly life of worms, ants, katydids and wetas. They were all her pets. Then she worked her way up through to geckos and lizards.

She had human friends too, they used to have their clubs and associations, and so on, but the creatures were a special area which no human could come near. It wasn't a secret but it was a very private thing. She was protective and possessive over what she called her little children, her spirit friends. She discovered they had just as much personality in their way of life as human beings, but were somehow more attractive, more interesting.

As she grew older, the animals grew larger. When she was 10 she was keeping birds that she'd rescued or nabbed from nests, a blackbird or a thrush or a sparrow. Later on it became opossums, and magpies. She brought them up from infant stage. She was their mother. They were always very free. She would take them out to the garden, and sometimes to school, hidden deep inside her. If she was mothering a small opossum she would keep it with her in her clothes. It was really fun. The kids would often find out and sometimes the teachers would too.

She's not sure now why she did that, but it gave her a sense of sanity, a type of vision other than the education being given her by the nuns of the school. She could never quite believe in school. She had an different attitude to life. She could never believe what she was being taught. She had already decided she was going to choose her own way. When she read A.S. Newell and Krishnamurti at the age of 13, she found an affirmation of the path she'd decided on. Then at 14 and a half she discovered Karl Jung, and Conrad Lawrence. She felt her way of perceiving life was correct and had some deep truth in it.

Another part of her life, outside of school, was spent around the coastal landscape. Her mother gave her children a lot of freedom and they lived very close to a wild part of the ocean with lots of hills. Her parents had a place in Titahi Bay and Victoria grew up there, in between staying with her Grandmother in Thorndon while she was going to school.

It was a split sort of life. At Titahi Bay it was like a savage alternative lifestyle, doing all sorts of crazy things around the coasts, wild rather than primitive, and really, really curious. In this way she slipped away from this modern civilization, this way of seeing life in only one dimension.

Her inheritance of contradictions from her family opened up other ways of seeing. She became aware of phenomena that were not perceived to be part of reality or to have any impact on reality in itself. Her dreams became part of her experience.

* * * * *

In her teenage years she still felt a kinship with creatures. At the age of 15 Victoria pierced her nose and put a ring in it. People may have thought her retarded, but she was feeling a slow evolution into adulthood. She felt it in her mind and in her soul. It was a gradual process and required certain forms of teaching that she couldn't find in the education system.In her latest work, which resulted in her book of photographs The Spirited Earth (Rizzoli New York, 1990), she found that other peoples did offer ways of maturing through their initiation ceremonies. But in Western civilization you go through baptism when you're an infant and that's it, you're cleansed. If you have a good life, if you're a loyal and obedient citizen to the ruling powers, your place in heaven is guaranteed.

She was introduced to photography by a family friend who took photographs of her and other children. He didn't show her how to take photographs, but he let her borrow the camera, a 35mm Leica. She taught herself. She can still remember the first photograph she ever took. Victoria thought it was wonderful. A wild seagull was attacking her friend. In the frame you can see the beautiful wings of the bird brushing over the head of somebody whose hand is reaching out. A powerful image of a bird in a form of attack. She was 16 when she started taking photographs. She went looking for stark, dark images in black and white. Some of them definitely had a feeling of - doom is not the right word, but a quality of darkness.

She read a lot, but she never looked at photography books. She had no formal training. She found out about exposures and the tricks of the trade by trial and error. She used to print her own images but never very well. She was aware of her failings there. She got good images but she couldn't print them well. She used to love going into the darkroom after travelling. After getting intensely involved with people, tribal people, myth people, she could withdraw into the dim silence, and bring herself back in. Now that she photographs in colour, with its more demanding developing process, she doesn't print her own photos any more.

She was never a commercial photographer. She showed prints to her friends and had a few exhibitions, but she never sold any. School hadn't educated her on how to market herself. In her early work in New Zealand she used to choose certain individuals and befriend them. There was an old lady who lived up Aro Street in a dark damp valley with dilapidated wooden houses that had the paint peeling off. The old lady was covered with warts, the skin on her face and neck sagged and bulged with the weight of them. When Victoria was 20 she photographed the old lady eating and became her friend. She could see such a power in the old lady's ravaged face. It had an immense amount to say.

On her journeys through Afghanistan and Pakistan Victoria noticed how the maimed and retarded were treated. There was a sense of sacredness surrounding them as the crowds surged backwards and forwards around them with ceaseless energy. Those were the sorts of people she was drawn to. Not necessarily maimed, just a quality that she sought. It might be a smile that seemed to be extremely pure, rich in something, where the soul seemed to shine through, where there was no artifice or half life. It may be somebody who'd become mad, but there remained a pure sense of that person's self even though they'd lost consciousness of their personality. That didn't matter. Personality to Victoria was a superficial thing. She wanted to get behind personality, that obvious self we coat ourselves with to keep going, to fuel our sense of belonging.

Then she became interested in the show and play of light, and what effect it had on mood and emotion. She felt she was dealing with a universal archetypal language of the individual. Her early work repelled many people because it was stark, black and white, full-on, with nothing oblique. To her the world was full of zombies, a land of concrete and gray suits and stiff staring faces that never met you with honesty. The only people who contained the real purity of life were people who didn't belong to "normal" society. This was her view of New Zealand in the 1970s.

* * * * *

Victoria spent a lot of time climbing hills and wondering if she could survive and live in the bush where she didn't need to be dependent on human beings at all. But she used to feel the loneliness there too. She could never figure out what that loneliness was until she went into other jungles and dwelt amongst the people who had lived there for generations. Then she knew.She thinks the spirit of the people has gone from the New Zealand bush. They're no longer picking the berries. You don't meet them on the paths in the bush dressed in beautiful leaves walking with lovely grace and smiling faces. New Zealand had a sense of terrible loneliness in its hills. At the same time, she refused to be defeated by that. Because that's where she belonged. This was the country she had been born into.

But first she had to get out. She felt she was only going round in circles, little circles in a little country. She left when she was 19 and went to England and Canada, finishing up in Florida with an aunt who taught her the proper ways to dress. She was suddenly blasted out into the great wide world and she started to notice the effect on people of how one dressed, the differences in attitude that resulted. She was in Florida amongst a closed circle of retired millionaires. She would have shamed her relations if she'd kept to her own indifferent ways of dress. She didn't want to do that, she wanted to show respect. She allowed herself to be remoulded for a time. She didn't wear a ring in her nose anymore.

On her second journey, a couple of years later, she went to South-East Asia and there she was introduced to the life of the night. It was quite different to anything she'd experienced before. It was a kind of wonderful chaos. She was at a romantic age and was open to the mystery and all the excitement. She wanted to explore and take photographs. She wanted to open up her whole self. Photographing was her way of responding to people.

When her Grandmother died Victoria took over the house in Thorndon. It became her base. She took in boarders but tried to retain its sense of home. She kept the music room. The house had a wonderful sense of atmosphere. She needed that base. She always needed a long period of rest after her adventures travelling. She didn't go on package tours. Her travels were open to the winds. Whatever happened, happened. They were rich in adventure, with touches of drama and confrontation. She used to leave for relatively short trips, six or eight months, just exploring or trying out another lifestyle. Then she'd come back to the house.

One trip took her to Papua New Guinea. It was her first really beautiful experience with another people. She didn't know where she was going but somehow she ended way up on the border between Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea where the Hulo tribe lived. She seemed to have stepped back into pre-history. All her early life disappeared, vanished. She couldn't speak their language, but she didn't need speech, she didn't need to talk. The tribe communicated silently, through the eyes, through face reading, through gesture, through gut reaction. In this way she met a lovely people who in their own tiny space seemed to go back fifty or sixty thousand years.

She fell into that space. It was like falling into a time warp. They were a pure people. They had something that had never been altered. They had a sense of identity, a sense of belonging to their land and to the spirits and to the magic of the place. She spent only a few months there, but it was enough. It could have been an eternity because the experience was so intense.

In New Zealand time had just drifted by. In a year she may have had only three or four experiences that had an intense effect upon her and remained in her life for a number of years. But when she travelled, in a month she could experience something that seemed to cover a whole lifetime because it was so full. It was a blast.

She used to go on journeys in her dreams too. She had epic dreams that she would remember for years afterwards. Sometimes she found, when she went on a journey, especially in Afghanistan, that she had already been there. She recognised, not the cities, but the landscape, because she'd seen it already in one of her dream journeys. It happened in Australia also, in the Northern Territories, the ancient and wild areas of the outback there. Her dream journeys were the other half of her travelling self. She never dreamt when she was travelling. She sometimes grew weary of having to travel physically because she knew of this other way. But she had to travel physically in order to bring something tangible back.

She had the power to read minds for a time after coming out of Papua New Guinea. She had a sense of horror as she looked at people. She witnessed the deterioration of some artist friends. They were writers and musicians. She saw them decline into insanity while nobody seemed able to help. There was nothing to nourish the soul. She watched madness encroaching on people with highly refined sensitivities. One was a particularly close friend. She felt very quickly she had to escape.

* * * * *

Victoria went to Afghanistan. She was drawn there because it's an ancient country where visionaries and mystics of another, intense kind exist. She encountered many extremes and contradictions of reality, of what reality was supposed to be. All sorts of guides and helpers appeared out of nowhere. And she saw the wonderful beauty of some of the people. There was something so special about them, but at the same time they had an extraordinary brutishness and backwardness, and just plain stupidity.Then it happened that she became a prisoner of the Afghanistani justice system. Fortunately she made a friend who became her helper. He was a landowner and a doctor, an intellectual, part of the old aristocracy. He had to pretend to be an interpreter from the British Embassy, otherwise he couldn't be seen with her. He helped her fight to get her freedom back. It was 1978, when the Russians moved in and the revolution began. Because she had to organise her own trial she witnessed what was going on. She was moving in and out of the ministries and courts of justice and meeting with judges and prosecutors.

The very day the Russians invaded she was sitting with her helper in the Supreme Court Chambers. They watched the leader of his outlawed political party being arrested and brought in. Two other senior members of his illegal party had just been shot. When her helper saw the leader being taken in, he thought that was it. That was their only hope for a more democratic government. He was full of despair.

They went out and sat in a coffee bar where they could talk. He said, "I will raise the people of my area. I can raise 70,000 soldiers." He was so upset. "I'm going to organise a revolution," he said.

She told him there had to be another way. "It's not the way to go," she said. "It won't work."

That afternoon Victoria met her judges. She had afternoon tea with them, sitting on soft cushions in a big courtroom with High Court judges dressed in turbans. They assured her that she'd be let free the day after next. Victoria went back to the cheap hotel she was staying at and thought, "At long last."

She'd had so many false hopes. From the day she was imprisoned they would say, "Tomorrow you're going to be released." They would pull her to the grate and say, "Tomorrow you'll be let go." Tomorrow would come and the guards would lead her to the courts where there were 40 or 50 prosecutors, and maybe one could speak English. They would discuss her case with the one that could speak English. Then he would tell her what they were going to do. They were debating whether she should have a trial or whether she should just be left in prison. They were going to take her cameras away. They tortured her in this way and reduced her to tears.

This went on daily. And every day she'd think, "Maybe tomorrow I'm going to be free."

Eventually she got out on bail. She had to stay in a special hotel on the outskirts of Kabul. A cheap single-story mud cottage that cost only 20 cents a night.

When she was in prison she was safe. She was protected by the women. When she was out, she wasn't protected by anybody. She was at the mercy of prosecutors or anyone who had her file. She was a prisoner of 200 clerks and prosecutors and judges. They knew that when they had her file they had complete power over her. Being white, not Muslim, an unmarried woman, supposedly guilty of a crime, she was nothing. When you're in a state of nothing, how can you protect yourself against the huge army of lust and hatred that was thrown at you? She would have preferred to have stayed in prison.

Victoria was sitting in the courtyard of the hotel, on the outskirts of the city, drinking a cup of tea when she heard guns in the distance. She had said goodbye to her helper, and the judges had said, "Tomorrow." This time it was going to happen.

She thought, "Now, for the first time in weeks I can relax." A servant boy brought her tea. Usually it was rich in sugar but she didn't buy sugar this day. Big fat ants climbed up her legs to drink her perspiration because it was so hot. She didn't mind the ants crawling up her legs. They could crawl all over her because the next day she was going to be free.

Then she heard the guns. They kept coming closer. After half an hour or so, when the servant boy came round with another cup of tea, she asked him, "Is this a celebration, all these guns?" Because the only time she had heard guns was back in Wellington on Queen's Birthday weekend. They sounded like the same guns - boom, boom.

"No, no, no," the boy replied. "Revolution."

Victoria sat there. She couldn't believe it. It just didn't register. She'd never been in a revolution. Revolutions belonged to history, in schoolbooks.

The booming came closer. After a while she heard a roaring up and down outside the hotel. She thought, "They have tanks moving around out there. I better go and have a look."

She didn't have her own camera, so she grabbed one from some Danish tourists who were in the hotel. Right outside the gate there was a tank with the tank driver poking out of the top. The driver looked like he was part of the metal, his body was so rigid, an angular, stiff tautness about him. She thought, "This is amazing to see, a man and machine become so much at one. I want to photograph it." It wasn't for political reasons, it was just the image. The servant boy was waiting behind her because he wanted to shut the gates.

But as soon as she lifted up the camera, a White Russian soldier jumped out of nowhere and grabbed her wrist. He hissed in her ear, "If you take one picture, you're dead."

She thought, "What?" It didn't register. The servant boy grabbed her camera. He was going to throw it on the ground. It wasn't even her camera. He was shrieking, "No, no, no, no, no."

She backed away towards the gates. As she backed off, she looked up the street and saw an exodus of people. She realised she had seen it already. She had dreamt about it a couple of years before. All the pieces of her dream were coming together. A huge exodus of people going out of the city. The street was closed. All the shops were shut, everything was barricaded and the people were gone.

Soldiers were swarming over the hills, like the red ants that climbed up her legs. They were coming over the hills around Kabul in their thousands.

She couldn't leave. It was too late. She couldn't get out of her street. They were lining up for war. She'd never been so frightened in her life.

A couple of people dashed in just before the gates closed on them. They were absolutely stricken. They'd just seen people being ripped in half by tanks rolling up and down the streets, not caring about civilians. They'd watched little boys being shot when the machinegun fire started. They were in a state of shock. "This is death," they cried. "Death is coming."

All the noises you hear in war films and documentaries erupted around her, the bombs whizzing through the air, and the deadly silence. They bombed the palace close by and there was heavy ground fighting. Every form of artillery made since the Second World War seemed to be taking part. Debris was falling everywhere. The people in the hotel, and the Danes, were huddled together. She thought it would be her last image of civilised people, all huddled together as a group, sheltering like animals in a corner of the hotel. Everything in the hotel was trembling.

Victoria went back to her room. The hotel was only a shack made of mud and straw divided into mud rooms. There was no protection.

Bombs fell everywhere. The hotel shook.

Then the jets screeched overhead. That's when she dived under her bed. The bed was about a foot off the floor, built of matted, woven straw. She discovered that if there's anything in modern warfare that's designed to destroy one's courage, it's the sound that low-flying jets make when they bomb. It's not the bombs themselves. It's the scream of the machine. The shriek as it dives only 50 feet overhead. The noise shattered her body and her nerves. She couldn't control herself because of the horrendous sound.

They bombed all night. For four days no one could go out. It had started on a sunny day, but as soon as the fighting began great clouds covered the sky over and it rained continuously. Just like that. Up till then it had been one long series of hot sunny days.

* * * * *

When she got back to New Zealand after this experience she looked around and thought, "These people know nothing about life." She felt such a softness in them because they had not experienced the extremity of life. Except occasionally at parties when she met men who had fought in the Second World War. Twice these older men started off smart, all-knowing, but were suddenly weeping as they talked. She knew exactly what it was they were going through.Victoria had nightmares for months after Afghanistan. If she wasn't being visited by ghosts, she was having dreams of the land filled with flames, or trying to escape from bombs, or hounded by prosecutors, or people pointing guns at her just about to shoot. It seemed there was nowhere in New Zealand, no one, nothing, to lead her forward into some more positive atmosphere. She had to create her own healing. She had to reconnect with life. She turned to the landscape and to the human spirit, the soul, the emotional self, reacting to and with the landscape.

That's where her colour work came from.

She became hyperconscious of life. Black and white was too interior. Now she wanted to see the skin of life, to feel the blood of life, to see the heart. She was responding in a different way, or perceiving in a different way fromher black and white photography. She had to cleanse herself of an evil that had been absorbed.

It went right back to the sense that the landscape shouldn't be alone. It was like the religious belief of ancient Indian philosophy, that nature has to be stimulated by the souls of humans interreacting with it. It was like being out on a mountain and your eyes are filled with the vision that you see. She wanted to say, "Where am I in this? Where is the emotion? Where is the human response?"

Maybe it wasn't even that. Maybe she was just trying to place herself in that land. That's why figures appear in her next work, The New Zealand Series, colour landscapes populated by strange fantastical human shapes. A trouserless jester dancing on wheat stubble. A naked figure submerged motionless in a tidal pool. A savage mud-caked madman baying at a gathering storm. It is like they're uniting in a psychic or sexual sense with the earth.

It was her way of healing. She couldn't passively sit and watch the land. She had to participate in it too. Or perhaps those strange figures were her artist self, doing it abstractly. In the same way the aboriginal man became the cassowary, the participation of the human soul with the soul of the earth. Healing requires the assistance of the force of nature, or the force that might be contained in an animal. Karl Jung has said nature is the one that cures, without which we are a neurotic animal.

That's one reason she put the figures in. But it was also because they looked right.

All that had happened before was like an initiation. All her experiences were a process of learning that prepared her for something else. Every work led to another work.

* * * * *

Victoria decided to take another trip. Her home in Thorndon was being sold and she wanted to get out. After Afghanistan she'd been trapped in New Zealand for six years. She was penniless, even destitute, for quite some time. She did her series of colour landscapes. She was ready for something else. It was like she'd been taught this lesson, now she was ready for - she didn't quite know what. So she prepared herself for the world of colour film and went off to Indonesia and it took off from there. She didn't know it would become a major book, she just saw it as another one of her projects.This time the journeys took more than three years, from 1984 through 1987. She had to return to New Zealand to restock and refinance. But it was all part of the same effort.

She finished up with representations from many different cultures. She went through parts of Indonesia. In Bali she found a lot of village beliefs and performance ritual, and the classical forms of dancing, storytelling through dance and drama left over by the reign of past kings. Myths were passed on by the courtly dance of Java. She was looking for the essence of what was behind the performance, the quality of the character, and what that represented on a psycho-spiritual social level.

She went into Sumatra and saw how they expressed their relationships to the land. Everything is linked to the sun or the moon or the ocean, or to the birds or animals, or to spirits of some form or other, or to gods or deities, energies within the psyche. She went through Sarawak up the rivers into the jungles and visited the various tribes. She happened, by chance, on major celebrations where people were seeking through their dances and rituals to unite with the various divinities of the jungle and sky.

She went through Thailand with its classic dance which served as a platform for the mythic characters of some of the great epics of Asia, the mythic epics of their religious history. On to Burma and Nepal and the religious festivals with their rituals, masks and forms of metamorphosis. Then into the Himalayan area of northern India with the Tibetan tantra, into the desert regions of central India, dwelling amongst tribal people and seeing their classical forms of religious expression that have been transformed through dance, becoming more like popular dance than the religious performance it used to be, but still retaining its sacred message.

The next journey took Victoria to northern Australia and north Queensland amongst the various aboriginal tribes there. Then over into the Solomon Islands where she was a visitor and guest of tribal people. Down into Vanuatu where you're not allowed to do these things without permits.

She didn't know a lot of the stories, the meanings, behind the ritual actions. When she took the photographs, she didn't know why she wanted the sea to be there, or why she wanted fire to be in the image. It was intuition. Later, when she researched them and found out their meanings, it all made sense. Every time. She would sense a delight in the performers when she suggested showing somebody representing the myth of the bird Garuda, the energy symbol for the Vedic Hindu god Vishnu, against a waterfall. It turned out the waterfall is Garuda's symbolic opposite which he is integrally involved with.

Each part of the journey prepared her for the next. She couldn't have done the second journey first. She wouldn't have had enough sensitivity. The Asians were a bit more flexible with her idiosyncracies and ignorance. All the while she became more sensitised. She had the feeling the gods and goddesses were looking after her. She still has that feeling.

All these journeys resulted in a book of photographs, The Spirited Earth: Dance, Myth, and Ritual from South Asia to the South Pacific, containing more than 160 colour photographs. It was published in November 1990 by a leading international publisher, Rizzoli in New York.

* * * * *

Someone once used the word void to describe to her how she worked. They said, "When you photograph, you seem to function in a void." Victoria thought of it as going in unguarded and very open.When Victoria went into a village they always took about a week, seeing what she was like, testing her. They would then decide whether to show her anything. She followed her intuition the whole time. She felt so often that she was one of them. She felt more at home - a strange feeling - than she did when she returned to New Zealand. She went into villages and met performers and priests and paramount chiefs who always greeted her with a form of ritual. It was body language and spontaneous reaction. She conjured up a lightness of being. A complex message was sent out through invisible antennae. Sometimes it was a sense of being embraced and embracing in return. She'd been expected. It was like that. She was meant to come, that was the feeling.

She was always being tested. The Tibetan Buddhists in northern India had amazing psychic qualities and powers. They tested her all right. She hates heights, they terrify her, but she had to go over the highest navigable pass in the world to try and find them. She didn't know why she was going there but she had to go.

She found herself in a bus winding up over a mountain trail teetering over sheer drops of five and ten thousand feet. The bus often had to go backwards in reverse, and cringe around one-lane unsealed surfaces to let lorries pass. The Tibetan passengers were all praying, using their prayer beads to get them safely over the mountain. Her eyes fixed with terror on the weaving of the woman's shawl sitting in front of her. She still has imprinted on her mind the detailed weaving of that shawl.

She climbed up to the monasteries perched high up on the mountain ledges in a valley leading into Tibet. When she got there, she found that the monks had all disappeared to go begging. They'd only just left. She had to go back over the mountain empty handed.

She went to the headquarters of the Dalai Lama in northern India, to Dharamsala where they had their refugee center. The monk in charge sent her in search of another monastery further down. This time the lamas and monks were there, praying. They were using the oldest, most pure form of Tibetan buddhist tantra that still exists. They told her she could take photographs but she had to come back in a few days' time after they'd finished their prayer sessions.

Every time she tried to return, the bus would break down. Day after day she set off for the monastery. Night after night she ended back up in Dharamsala.

In desperation Victoria went to the monk's office again. She told him, "There's something stopping me."

He said, "The greater something is, the more obstacles that will be placed in your way." He was trying to tell her she was meeting a power in these people, and that they would let her know when she was ready to come.

The change came after her final test. This time not only the bus broke down, but the taxi bringing her back broke down also. Victoria had to walk back up through the night, through the jungle bush. She'd crossed the mountain, feeling terrified again, then hired another taxi. It too broke down part way up the road to Dharamsala. She thought, "I'll have to walk back."

It was about six miles and she couldn't see. It was a pitch black night. She had to shuffle up the road listening to all the weird sounds coming out of the bush. There were crashes in the trees and the hoots and calls of baboons. She was tense and fearful, stumbling along in the blackness. She heard unfamiliar eerie sounds and thought, "What sort of monsters are these?"

After a while she began to relax. She thought, "I belong to this night, too. I'm all right. I'm a creature, they're all creatures. Nothing's going to hurt me."

She saw lights ahead of her. It was the Indian Hindu festival of lights and the village street with its little buildings was lined with candles. She came into the light with all these candles burning.

As she came out of the darkness the first thing she saw was a little child, dancing in the middle of the road. It was like a gift, something to lighten her burden. The child was dancing a dervish dance, or a Tibetan whirl dance, spinning himself around with a beautiful movement, then flipping himself over in circles, his many shadows skipping around him in the candlelight. It was exquisite.

She thought, "Here's my greeting. What a delight!" The child gave her a lovely sense of joy. She'd gone through her fear and found a state of peacefulness. She felt a change in her attitude.

When she tried to go down again the next day, it was all right. She had been the obstacle. It had been a form of initiation.

This time she reached the monastery without incident. She was content with the magic in her life.

1990

Tamu Nadu, India. Photo by Victoria Ginn